You can watch the full film on this link.

Inspired by John Moriarty’s iconic 2005 book INVOKING IRELAND (Áiliu Iath n-hÉrend), this film brings the legendary Poems, or Songs, of Amergin* to life for contemporary audiences.

According to legend the Poems, or Songs, of Amergin Glúngheal* are the first poems in Irish recited in Ireland. This film brings the poems to life in a kaleidoscope of images from Ireland’s past and present and with a chorus of Ireland’s finest living poets reading the poem in its original Old Irish including:

PADDY BUSHE, MOYA CANNON, LIAM CARSON, DAIRENA Ní CHINNÉIDE, ANNMARIE Ní CHUIRREÁIN, MICHAEL COADY, THEO DORGAN, AIFRIC Mac AODHA, LIAM Ó MUIRTHILE, GABRIEL ROSENSTOCK, DOMHNALL Mac SÍTHIGH

And features the voices of renowned Irish language scholars: PÁDRAIG Ó FIANNACHTA, and DÁITHÍ Ó hÓGÁIN.

This film was commissioned together with seven other films for a special season of Splanc! to celebrate and commemorate 2016 in art, in light of the centenary commemorations of the Easter 1916 Rising that led to Irish independence. Splanc! is the Irish language arts documentary scheme that supports the creative exploration of the arts in Ireland commissioned by TG4 and The Arts Council and administered by The Galway Film Centre.

* Also called The Song of Amergin in English

Amergin is written as Amhairghin in the original Old Irish.

Invoking Ireland (The Lilliput Press, 2005) is widely acknowledged as one of the key works of Irish writer, poet and philosopher, John Moriarty. Moriarty is considered by many as “a major writer, comparable to Yeats, Joyce and Beckett” (Guardian Obituary 2007). The book draws its name and inspiration from the legendary Poems of Amhairghin reinterpreted and re-invoked by Moriarty in what Declan Kiberd has described as “a reminder of the life-force that beats within us all.”

Moriarty’s landmark work does much to invoke the reverberating contemporary relevance of The Poems of Amhairghin to “the great ongoing war between matter and spirit” and reminds us that if all were right in the world The Poems of Amhairghin would rightly be the most famous of all Irish poems; for according to legend they are the first poems in Irish uttered on the island of Ireland. Sealing the significance of The Poems of Amhairghin is the fact that they emerge from “one of the most fundamental stories in Irish tradition: the account of how the country gained its official name ‘Éire’. ”

The Story of The Poems of Amhairghin

The legendary story of The Poems of Amhairghin is recorded in the eleventh-century Lebar Gabála Érenn, known in English as the Book of Invasions. It comes from The Mythological Cycle of early Irish literature.

The invading Milesian force – ostensibly the Gaels from Spain – consisting of thirty-six ships, arrive on Bealtaine (the first day of May) sometime between 400-700 BC and set anchor in Inber Scéne (popularly identified as Kenmare Bay).

On board are the sons of Míl, including the Poet-Seer Amhairghin Glúngheal. Setting his right foot on the land, Amhairghin is inspired to recite a magical incantation, his First Poem of invocation*;

Am gaeth i mmuir I am wind on sea

Am tond trethan I am wave upon land

Am fuaim mara . . . I am ocean roar . . . (excerpt)

Upon landing Amhairghin is inspired by the plentifulness of the land to proclaim his Second Poem of Invocation;

Iascach muir Fish-abounding sea

Mothach tír Fruitful Land

Tomaidm n-eisc . . . Irruption of Fish . . . (excerpt)

As the force make their way inland they meet the Three Queens of Tuatha Dé Danann who each request that they call the land by their name;

On Slieve Mish they encounter Banbha

On Éblinne they meet Fódhla

and on the Hill of Uisneach, at the heart of the country, the meet Éire

This is why in early times the land was known by these three names. Each, according to John Moriarty and Peadar Ó Riada, representing the three dimensions of the land of Ireland;

Banbha representing the creative dimension

Fódhla representing the spiritual dimension

and Éire representing the physical dimension (or the “overt, official dimension”).

Understandably the Three Kings of the Tuatha Dé Danann are not very pleased to see the invading force arrive at the centre of the country and respectfully ask the Milesians to return to their ships and grant them three days to consider their own position. The answer is left to the Poet-Seer Amhairghin and his pronouncement – referred to as the first judgement ever issued on the island of Ireland – affirms that it is only fair to grant the existing rulers of the land their request and that the Milesians should return to their ships and go out over nine waves beyond the shores for the allotted time.

However while the Milesians return to their ships, the Tuatha Dé Danann have other plans. They set their Druids the task of issuing forth incantations that conjure up a magical storm to prevent the Milesians from making shore again. But Amhairghin’s powers are a match for those of the Druids of the Tuatha Dé Danann and he issues forth his own powerful incantation, his Third Poem of Invocation that quells the storm;

Áiliu iath n-hÉrend I Invoke the Land of Ireland

Hérmach muir mothach Surging ocean swelling

Mothach slab srathach Swelling upland meadows

Srathach call cithach Meadow filled rain-woods

Cithach aub essach Rain-filled rivers cascading

Essach loch lindmar Cascading lakes spreading . . . (excerpt)

And so it is that the Milesians land and conquer the Tuatha Dé Danann who, in their defeat, shroud themselves in a veil of invisibility and retreat into the spiritual dimension of the land; “to the hills and the forests and the waterways of Ireland, taking all of their own magic with them”. And thus the final great mythical invasion recorded in Lebar Gabála Érenn comes to a close with Amhairghin’s Invocation ushering in a new era across the land.

Contemporary Relevance of The Poems of Amhairghin

Writing in the Oxford Dictionary of Irish Mythology, Peter Ellis describes the chant as an ‘extraordinary invocation to Ireland … in which Amergin subsumes everything into his own being, with a philosophical outlook that parallels the Hindu Bhagavadgita’.

Robert Graves, in his poetic manifesto, ‘The White Goddess’, contends that “English poetic education should, really, begin not with The Canterbury Tales, not with The Odyssey, not even with Genesis, but with The Poems of Amergin.”

Nuala Ní Domhnaill echoes her belief in the transformative influence of this “the very first Irish poem” in her afterword to Jan de Fouw’s book ‘Amergin’ published in 2000. There she laments “how the great wisdom … of the fifteen-hundred years of unbroken literary tradition that exists in the Irish language are an unknown entity” when “at this time of all times, it is of paramount importance that we acknowledge our oneness with the world and with all the creatures who share it with us … and bring about a new consciousness that will allow us all to survive and flourish.”

Paddy Bushe in his own 2013 translation of this ancient text echoes Ní Domhnaill’s call; “At our contemporary remove from the natural world . . . there is something here to which we should listen . . . As the mythological progenitor of Irish literature, Amergin makes the most direct possible kind of imaginative appropriation (as) poet, seer and lawmaker . . . he doesn’t just claim the landscape; he identifies with it . . . We need to learn again how to sink ourselves into the world we inhabit and Amergin’s poem can help us to do so.”

Contemporary Relevance of Invoking Ireland for 2016

“Taking his cue from Amergin’s invocation John Moriarty wants us to share his exploration of Irish myth at this deep psychological level so that we can find new meaning in the old stories … so that the old stories can bring a new perception to the way we live out our lives.” (Michael Harding)

“Invoking Ireland offers an alternative to the 1916 Easter Rising Proclamation . . . where all things live ecumenically with all things, uniting man with nature, magic and the divine . . . standing shamanically and mystically with the heroes of Ireland’s Dreamtime.” (From the cover notes to the book)

Anyone familiar with the Poems, or Songs, of Amhairghin will know that there are numerous versions – primarily of Poem 1 – available, so much so that it becomes a challenge to discern which may be the most reliable or accurate rendering of the original. Hence, for this film, it was important for us to go back to the earliest known surviving manuscripts – original texts written in Old/Middle Irish – and find accurate subsequent translations into English.

Thus began a journey through what Professor John Carey has accurately described as “the textual labyrinth” of Irish Mythology.

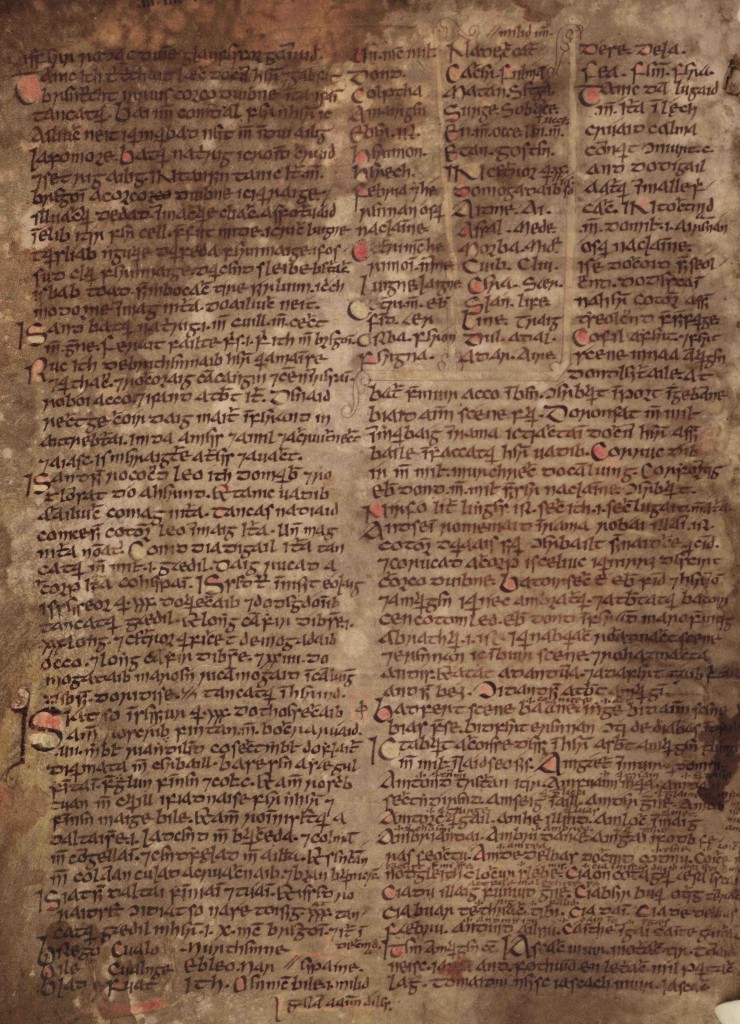

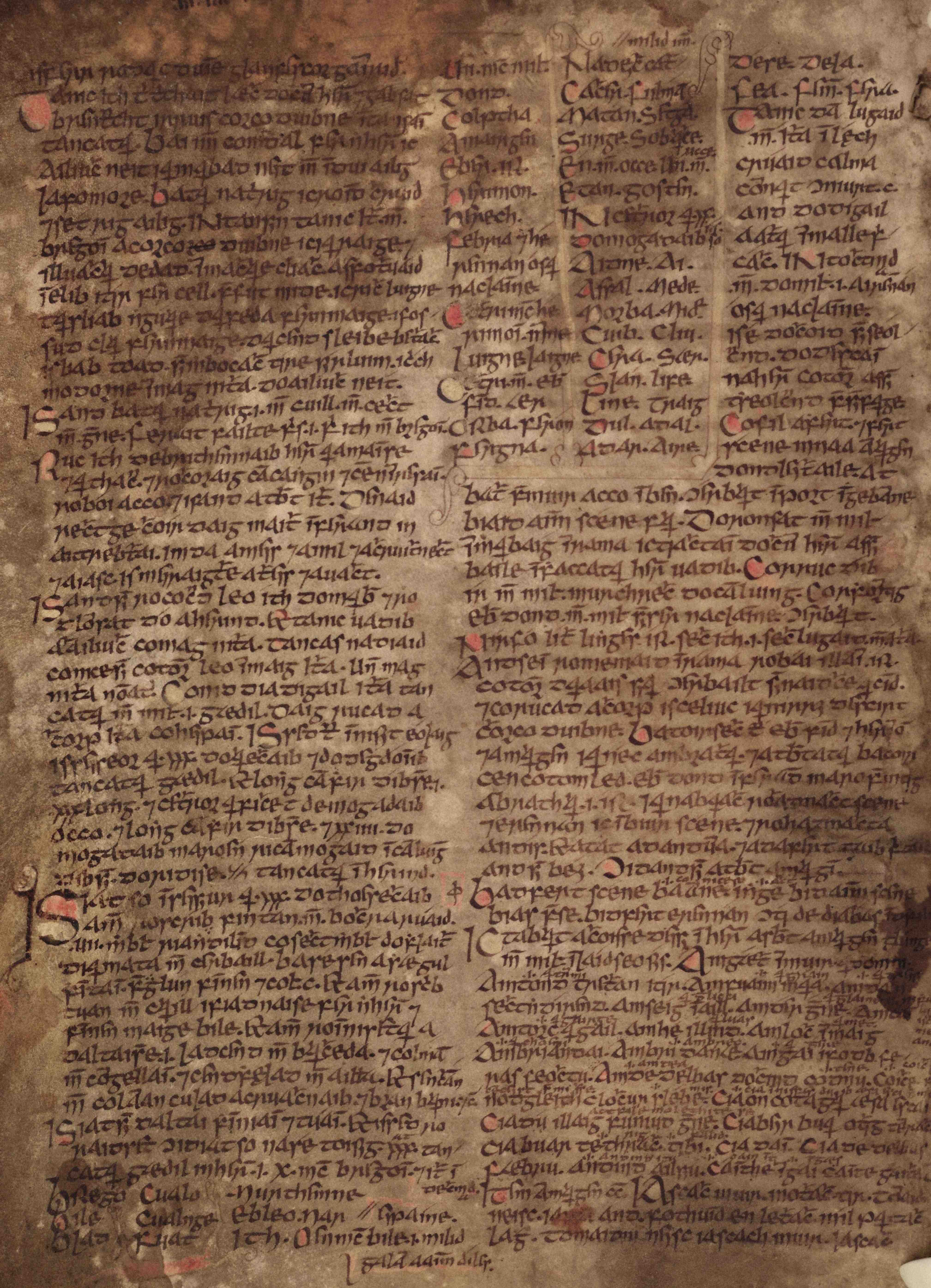

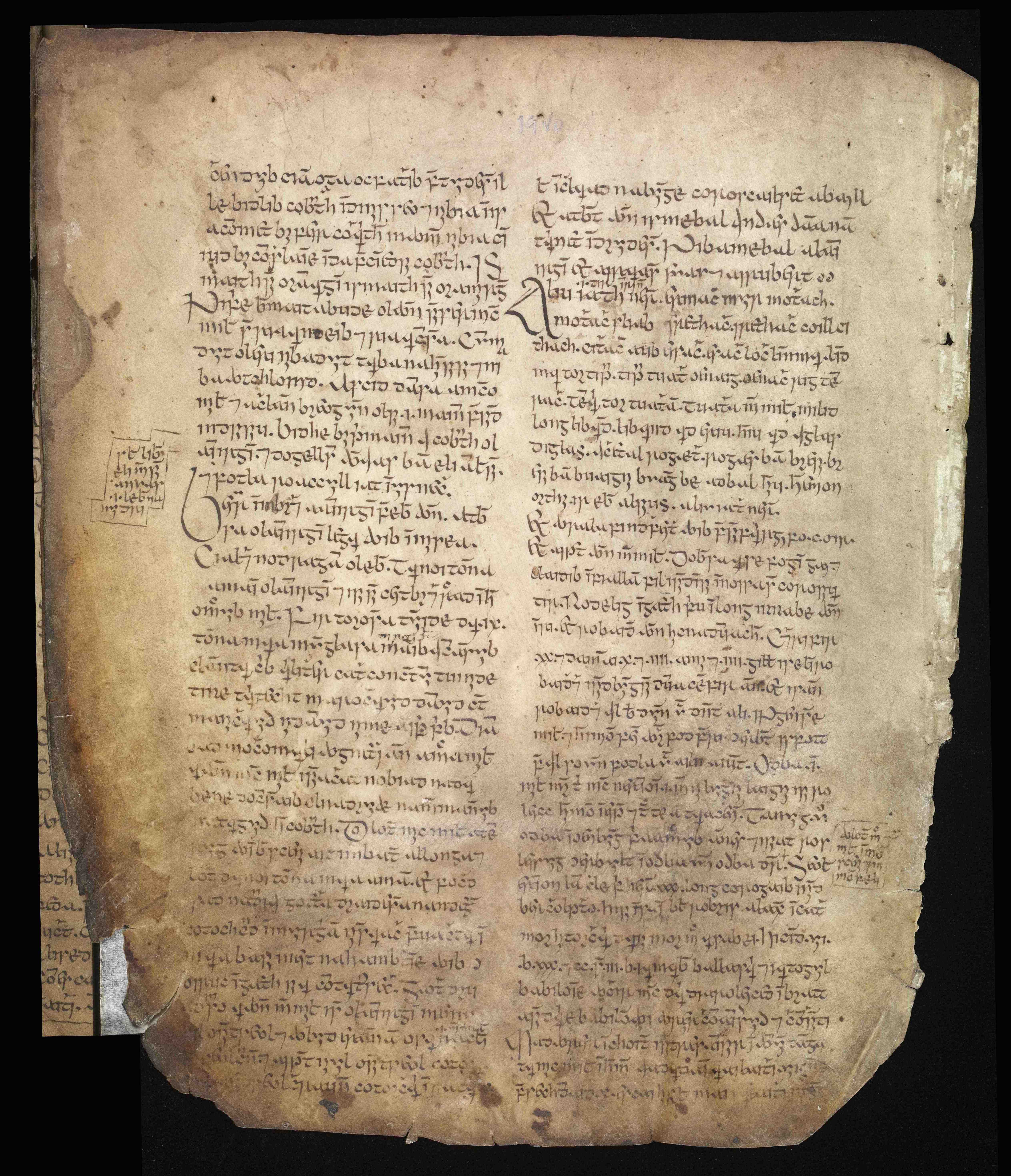

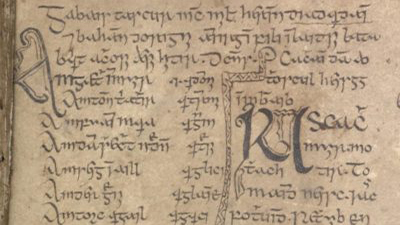

Excerpt from The Book of Leinster (ca. 1160) – Courtesy of TCD

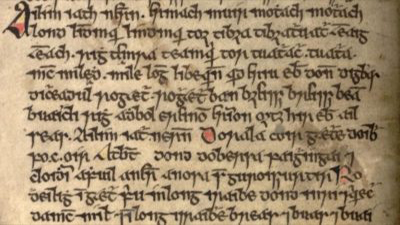

Excerpt from The Book of Leinster (ca. 1160) – Courtesy of TCD

The starting point began with the version included in John Moriarty’s 2005 book ‘Invoking Ireland’. However the book only includes the first six lines of Poem 3. As Moriarty credits Professor John Carey’s translation as a source of reference, we contacted John at UCC in January 2016 to begin the search for the original texts.

Over many subsequent meetings and communications back and forth throughout January and February 2016, John generously shared key aspects of the painstaking scholarly research that he had undertaken over the years.

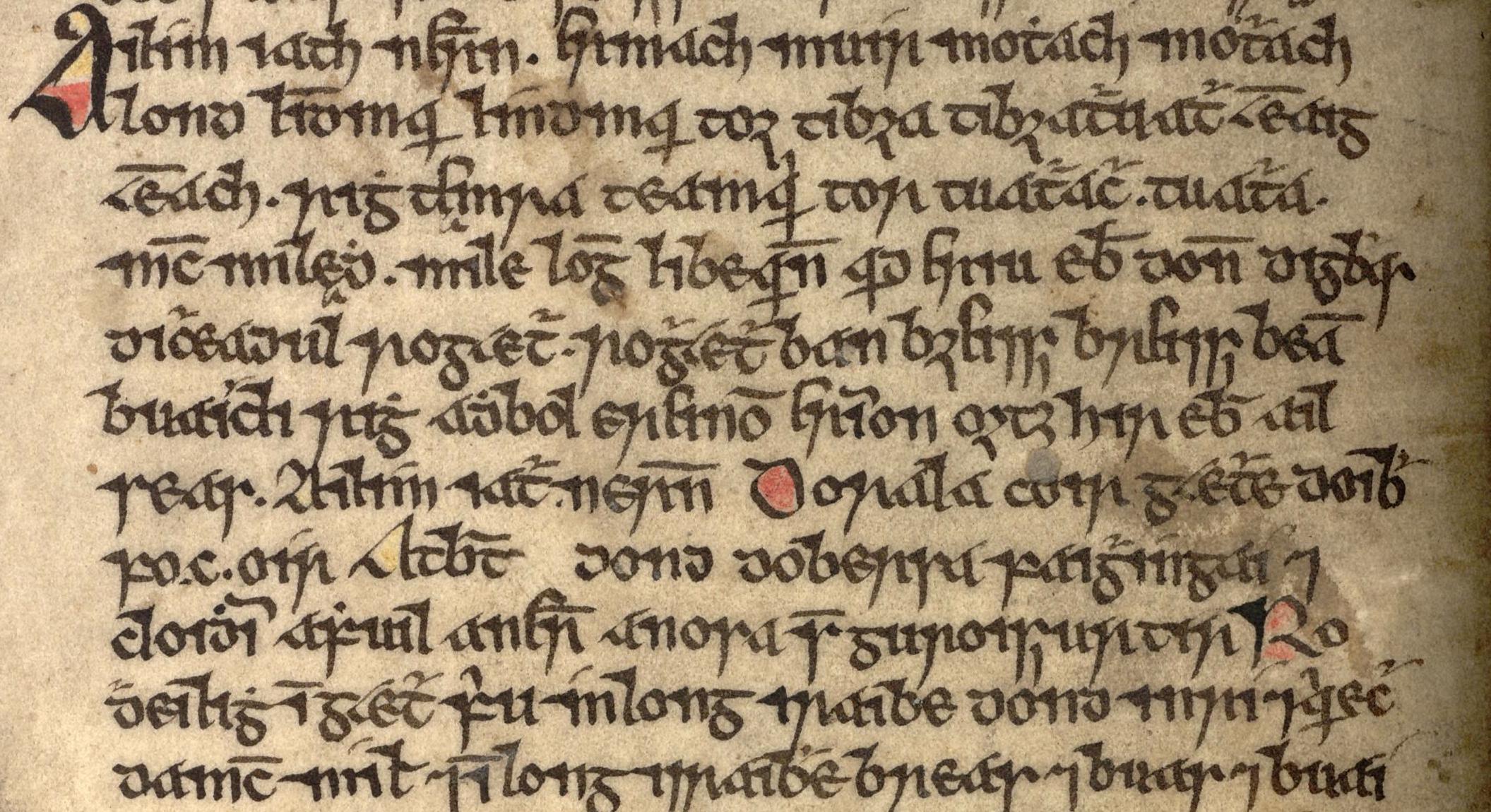

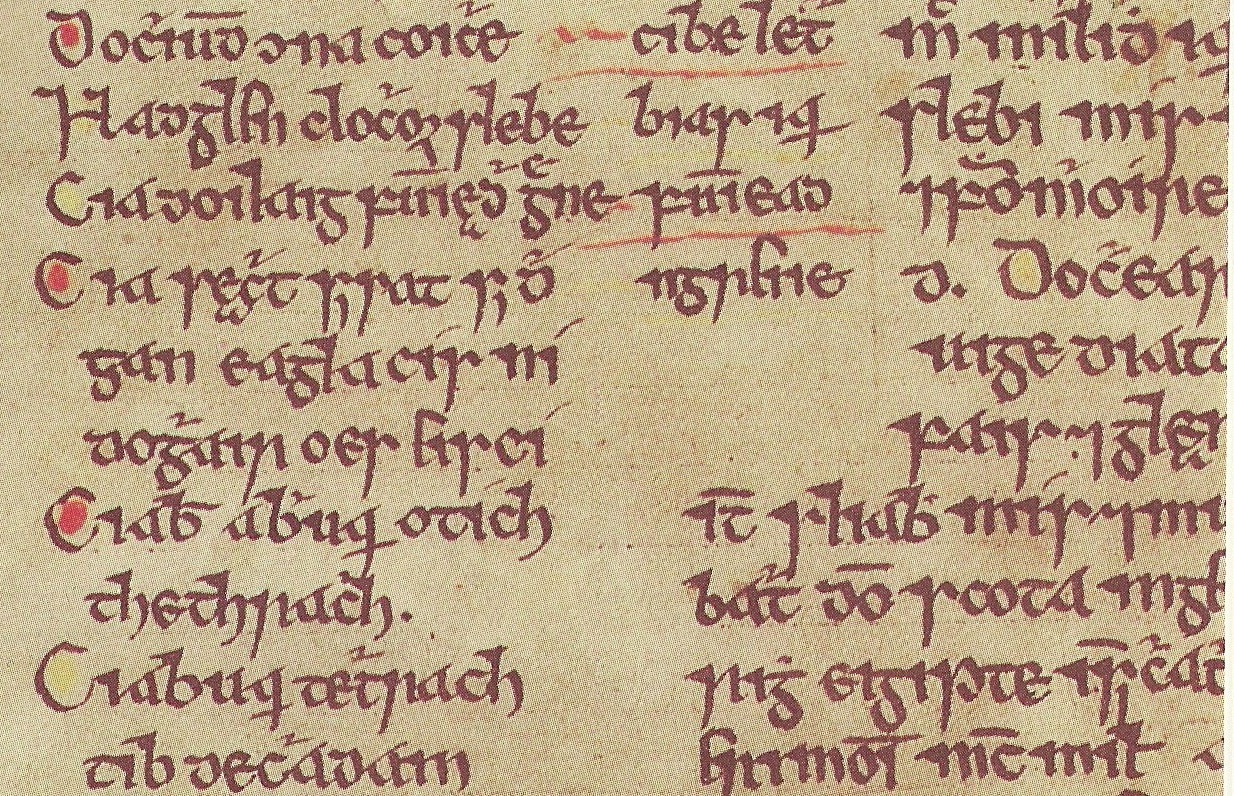

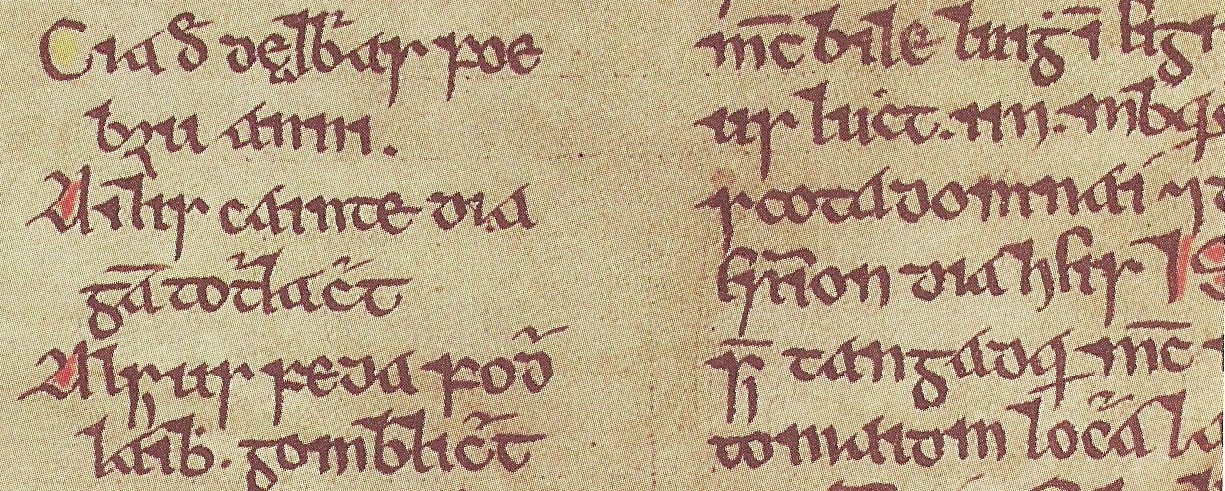

Thanks to John’s meticulous work we have the most accurate and reliable historical manuscripts and versions of the poems available in original Old/Middle Irish. These have been compiled by John from a comparison of the earliest existing manuscripts including:

– The Book of Leinster (ca. 1160) – TCD

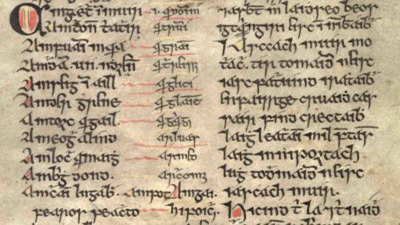

– The Book of Lecan (from between 1397 and 1418) – RIA

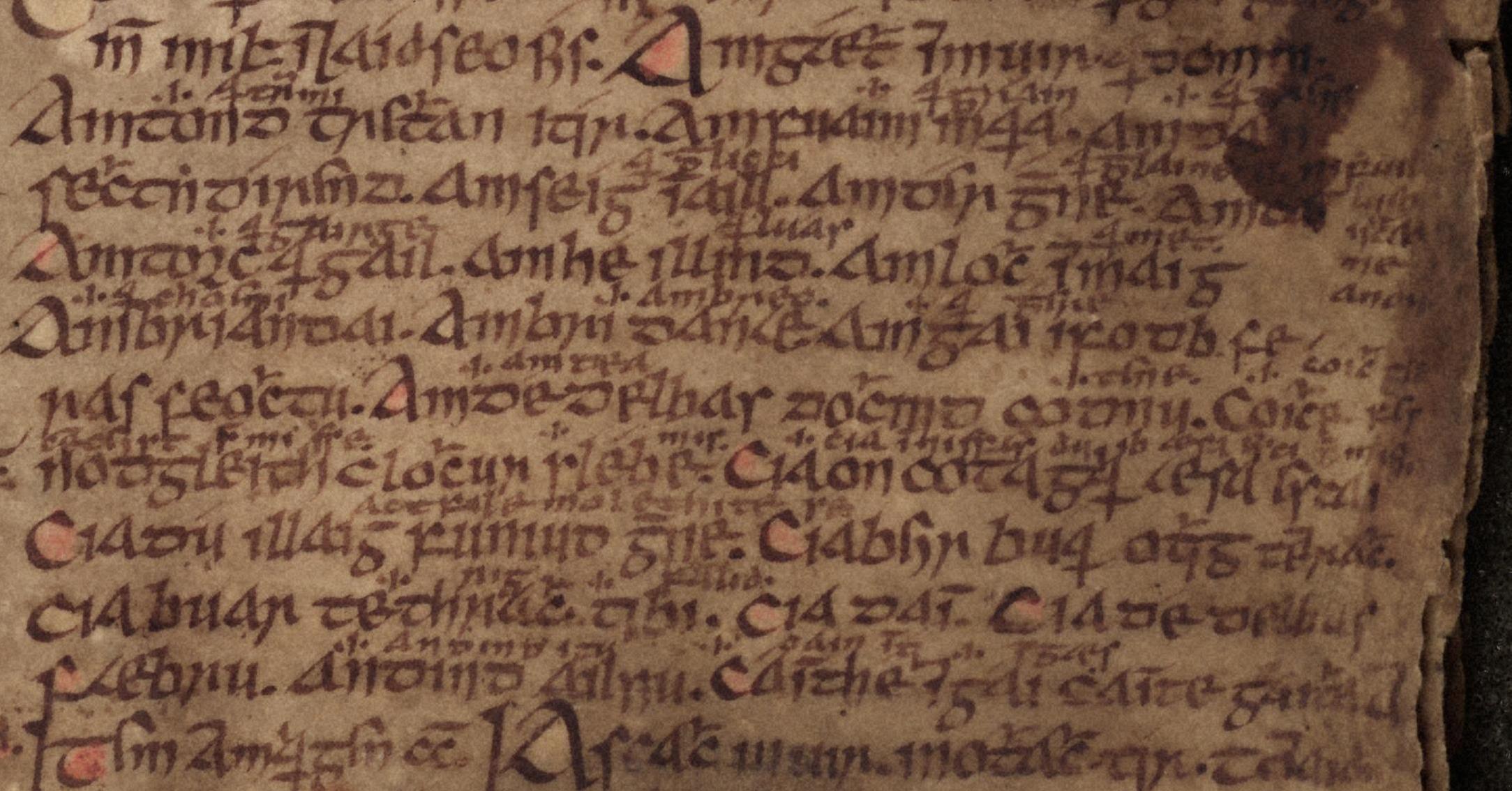

– The Book of Ballymote (ca. 1390) – RIA

– The Book of Fermoy (14th to 16th century) – RIA

& The Oxford, Bodleian Laud Misc (ca 1453)

Fortunately many of these manuscripts have been scanned page-by-page and specific manuscripts are now available to view online at Irish Script Onscreen.

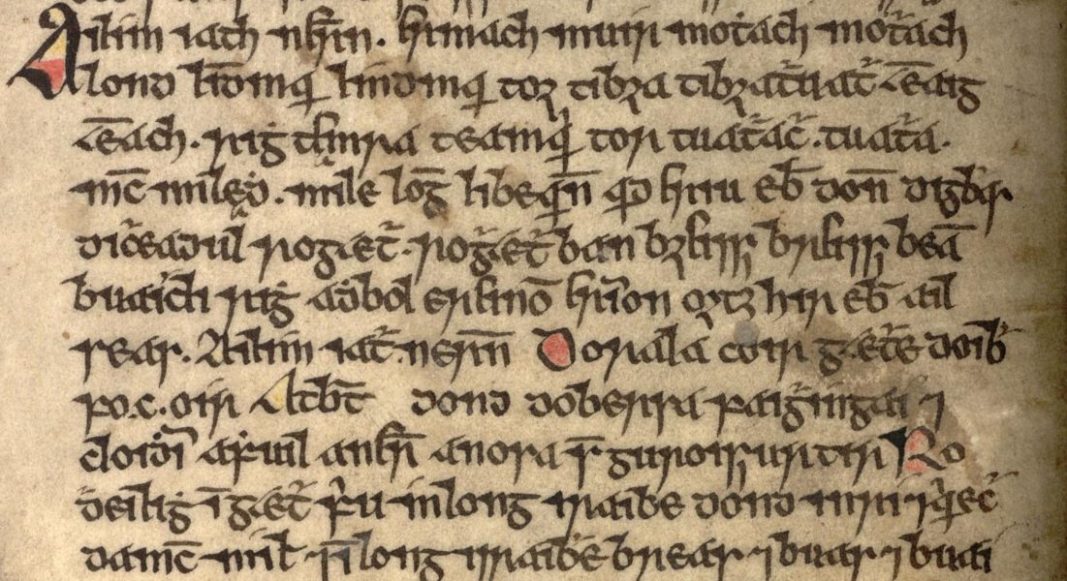

Excerpt from The Book of Leinster (ca. 1160) – Courtesy of TCD

Translations

Working from original manuscripts posed a problem in that, as far as we were aware, no complete contemporary poetic English translation of these original texts existed for all three poems.

Hence the English translation of the poems, included in the titles of the film, is a composite translation compiled specially for the film from the following key sources:

– John Carey’s scholarly translation included in ‘The Celtic Heroic Age’ (2003)

– John Moriarty’s translation included in ‘Invoking Ireland’ (2005)

– R.A. Stewart Macalister’s translation in ‘Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland’ (1956)

and from a spontaneous translation of Poem 3 made by Gabriel Rosenstock during production of the film.

Excerpt from The Book of Ballymote (ca. 1390) – Courtesty of RIA

Pronunciation

Pronunciation of the original text for anyone unfamiliar with Old/Middle Irish is probably as challenging as pronouncing Latin would be for speakers of the modern romance languages of Italian, Spanish and French. Pronunciation of the Old/Middle Irish is interpreted from scholarly phonetic comparisons of original texts and it was important for us that the film include as accurate a pronunciation of the texts as was realistically possible. For this challenge we were most fortunate to have two renowned scholars in the field; Professor Carey and Monsignor Pádraig Ó Fiannachta of An Díseart; a renowned Irish language scholar and poet born in the Kerry Gaeltacht in 1927.

We were also fortunate to have contributions from some of our finest living Poets.

Regarding the Poems’ Antiquity

“Early Irish literature is the oldest vernacular literature in Western Europe (vernacular here meaning written in the speech of the common people as opposed to scholarly Latin). Historically, it is unclear when literacy first came to Ireland. The earliest remaining Irish writings are inscriptions, mostly simple memorials, on stone in the ogham alphabet, the earliest of which date to the 4th century.

The oldest surviving manuscripts containing examples of the written Irish language date to the 8th century. Their Irish contents consist of glosses written between the lines or on the margins of religious works in Latin. Most of them are preserved in monasteries in Switzerland, Germany, France, and Italy.

The oldest books of miscellaneous literature are; the ‘Lebor na hUidre’, or ‘Book of the Dun Cow’, transcribed about 1100, and the ‘Book of Leinster’, from about 1160. The ‘Book of Leinster’ is one of the source manuscripts for Lebor Gabála Erenn and contains the Poems of Amhairghin. However, the date at which these manuscripts were penned is no indication as to when their contents were first written, and it is evident from their contents that many of them must have been orally transmitted for centuries before they were committed to writing.” (summarised from ‘An Introduction to Early Irish Literature’, Muireann Ní Bhrolcháin (2009))

Although the exact dates of origin of the poems and stories of Irish Literature are now lost to us in time, there is every reason to believe that these poems draw upon the origin myths of the pre-Christian Irish. This is why, as Douglas Hyde writes in his ‘Literary History of Ireland’, “Irish tradition has always represented them as being the first verses made in Ireland”.

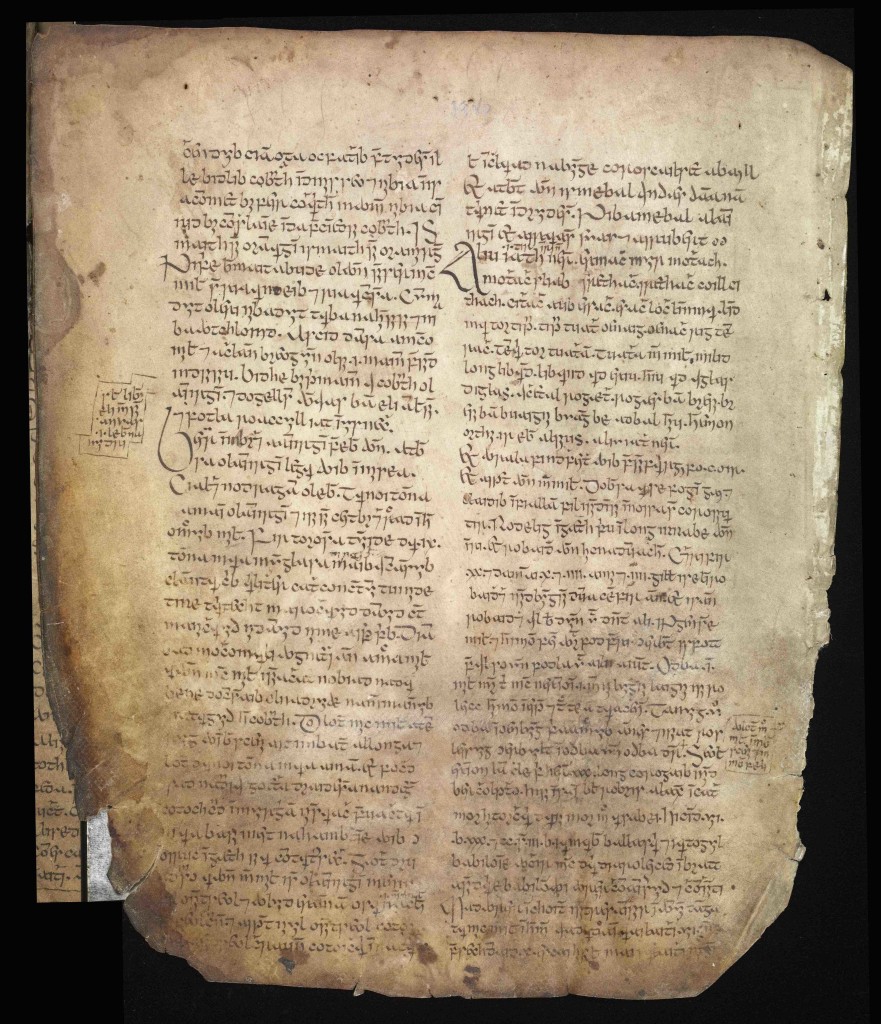

Excerpt from LEBOR GABÁLA ERENN (16th Century Vellum) – Courtesty of RIA

Excerpt from LEBOR GABÁLA ERENN (16th Century Vellum) – Courtesty of RIA

(Note that the Poem texts, drawn from original manuscripts, are in Old/Middle Irish)

Dán 1 / Poem 1

Am gaeth i mmuir (I am wind on sea)

Am tonn trethain (I am wave upon land)

Am fuaimm i mmuir (I am ocean roar)

Am dam sethair (I am stag of seven fights)

Am séig for aill (I am hawk on cliff)

Am dér gréne (I am tear-drop of the sun)

Am cain lubai (I am fairest of plants)

Am torc ar gail (I am boar for valour)

Am hé i llimd (I am salmon in pool)

Am loch i mmaig (I am lake on plain)

Am brí dánae (I am excellence of the arts)

Am gae la fodb feras fechtu (I am spear waging war with plunder)

Am dé delbas do chind codnu (I am a god who forms subjects for a ruler)

Cóich é nod gleith clochar slébe? (Who explains the stones of the mountain?)

Cia ón cota-gair aesa éscai? (Who invokes the ages of the Moon?)

Cia dú i llaig fuiniud gréne? (Where lies the setting of the Sun?)

Cia beir buar ó thig Thethrach? (Who bears the cattle from the house of Tethra?)

Cia buar Tethrach tibite? (Who or what are the laughing cattle of Tethra?)

Cia doen, cia dé delbas faebru? (What man, what god, forms weapons?)

Amin ám: (Then Indeed)

Áilsiu cáinte, (I invoked a satirist)

cáinte gaíthe (a satirist of wind)

Dán 2 / Poem 2

Iascach muir, (Fish-abounding sea)

mothach tír, (Fruitful Land)

tomaidm n-éisc, (Irruption of Fish)

iascach and fo thuind, (Fishing there, under wave)

rethaib én, (Flights of Birds)

lethan míl (Great Sea Creature)

portach lug, (Crab pool)

tomaidm n-éisc, (Irruption of Fish)

iascach muir. (Fish-abounding sea)

Dán 3 / Poem 3

Áiliu iath n-hÉrend (I invoke the Land of Ireland)

hérmach muir mothach, (Surging ocean swelling)

mothach sliab srathach, (Swelling upland meadows)

srathach caill cithach, (Meadow filled rain-woods)

cithach aub essach, (Rain-filled rivers cascading)

essach loch lindmar, (Cascading lakes spreading)

lindmar tor tiara, (Spreading spring of multitudes)

tipra tuath oenach, (A spring of peoples, an assembly)

oenach ríg Temrach, (Assembly of the King of Tara)

Temair tor tuathach, (Tara tower of tribes)

tuatha mac Míled, (Tribes of the sons of Míl)

mílid long, libarn, (Warriors of vessels)

libarn ard hÉriu, (This vast vessel Ireland)

Éber Dond díglas, (Éber Donn flourishing)

díchetal rogaeth, (Wise incantation)

rogaeth ban Bresi, (of the wise wives of Brese)

brese ban Buagne, (Outcry of the wives of Buaigne)

bé n-adbul hÉriu, (Ireland in her vastness:)

Hérimón ortus, (Éremon smote her)

Ír, Éber, álsius, (Ír, Éber entreated her,)

Áiliu iath n-hÉrend (I invoke the Land of Ireland)

Ascribed to Amhairghin Glúngheal (also called Amergin in English, whose first name is translated as ‘Born of Song’)

Agus Le Monsignor PÁDRAIG Ó FIANNACHTA

Agus Guth DÁITHÍ Ó hÓGÁIN, Beannacht Dé Leis

An Cailín ar Cnoc na Teamhrach DANIELLE Ní RIAIN

Guthanna na bPáistí SÍLE Ní MHEACHAIR, EAMONN Ó MEACHAIR, DYLAN De FAOITE, ROISÍN Ní RÍORDÁIN

Ceamara PATRICK JORDAN, DÓNAL Ó CÉILLEACHAIR

Ceamara Cúnta TOM BYRNE

Dathadóir Agus Eagarthóir Líne KIERAN FITZGERALD

Meascadh Fuaime CONOR BARRON, HALF-LIGHT AUDIO

Comhairleoir Cruthaitheach ALAN LAMBERT

Eagarthóireacht, Dearadh Fuaime agus Taifeadh na bhFilí DÓNAL Ó CÉILLEACHAIR

Comhairleoir, Gaeilge na Meánaoise PROF. JOHN CAREY, UCC

Aistriúcháin na nDánta ó:

‘The Celtic Heroic Age’ le Caoinchead ó PROF. JOHN CAREY, UCC

‘Áiliu Iath n-hÉrend/Invoking Ireland’, by JOHN MORIARTY le Caoinchead ó THE LILLIPUT PRESS, DUBLIN

Lebor Gabála Erenn le R.A. STEWART MACALISTERl e Caoinchead ó Chumann na Scríbheann nGaedhilge

Agus GABRIEL ROSENSTOCK

Iomhánna ó na lámhscríbhinní bunaidh le Cead ó

THE ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY © RIA and TRINITY COLLEGE DUBLIN

Le buíochas le Irish Script On Screen, School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies

Cartlann le Caoinchead ó

IFI – Cartlann Scannán na hÉireann Bailiúchán Gael-Linn, Bailiúchán Jim Mulkearns, Bailiúchán Vincent Corcoran, Bailiúchán Fr. Jack Delaney

EARTH HORIZON PRODUCTIONS

Agus PEADAR Ó RIADA

Iomhánna ón Scannán ‘PUSHTAR’ ó 2015 le Caoinchead ó ALAN LAMBERT, Stiúrthóir

Taifeadadh Cartlainne le Dáithí Ó hÓgáin le Caoinchead ó BILL FELTON

Ceol ó PEADAR Ó RIADA

‘Ómós Don Sulan’ Óna dhlúthdhiosca ‘Winds Gentle Whisper’

‘Im Long Me Measim’ Le CÓR CHÚIL AODHA Óna dhlúthdhiosca ‘Amidst These Hills’

‘Billy’s Breakfast Le MARTIN HAYES, CAOIMHÍN Ó RAGHALLAIGH Óna dhlúthdhiosca ‘Triúr Arís’

‘Agraím oraibh (go deireadh)’ Le CÓR BAN CHÚIL AODHA Óna dhlúthdhiosca ‘Laoi na Laoithe’

Agus ceol bunaidh © PEADAR Ó RIADA | Publishing REAL WORLD

Míle Buíochas le JOSEPHINE QUINLAN, ANN Agus PHILLY NÍ RIAIN, JERRY QUINLAN, MICHAEL, CATRÍONA agus Muireann QUINLAN, NUALA NÍ DHOMHNAILL, MARY O’MALLEY, FRANK GALLIGAN, SANDY DUNLOP, Bard Mythologies, CLANN UI MHEACHAIR, CLANN UI RÍORDÁIN, CLANN De FAOITE, MÁIRE Ó GRUAGÁIN, NEIL HURLEY, BRENDAN O’DONOGHUE, OPW : The Hill of Tara – PATRICIA RYAN, WILLIE FOLEY, Ionad Cultúrtha, Baile Mhúírne, Co. Chorcaí, Cork Film Centre – CHRIS HURLEY, IFI – RAELENE CASEY, The Lilliput Press, Dublin – ANTONY FARRELL, Galway Film Centre – DECLAN GIBBONS, An Chomhairle Ealaíon – MARETTA DILLON, FIONNUALA SWEENEY Agus PROINSIAS NÍ GHRÁINNE, Eagarthóir Coimisiúnaithe, TG

Scannán Le DÓNAL Ó CÉILLEACHAIR

Ceol PEADAR Ó RIADA

Léiritheoirí MARTINA DURAC, DÓNAL Ó CÉILLEACHAIR

MAR ATÁ AONTAITHE LE TG4 AGUS AN CHOMHAIRLE EALAÍON